The brand spanking new electoral system the UK is crying out for

We can blend proportional representation and first-past-the-post into something beautiful

This post contains interactive data visualisations — it’s best viewed on a computer.

I’ll admit it: I only set up this Substack to enter a competition. Very touchingly, 37 of you subscribed for further updates. If you’ve been refreshing the site regularly, hoping for some new content, then I’m sorry. (Competition result: joint third).

I’m still absolutely not planning to write regularly here. But I did have one idea, about two years ago, that hasn’t left me alone. It’s for a new electoral system, so an election actually being called has given me the shove I needed to get on and write it. Then I’ll at least know that I floated it upon the vast ocean of ideas, and if it has merit perhaps it’ll end up somewhere.

Like many people, I find some of the flaws with our First Past the Post (FPTP) system pretty glaring. Our parliament grossly exaggerates the bigger parties and punishes the smaller ones. Millions of votes go to waste. Lots of people vote for their least-worst option — rather than what they’d actually like.

Not only that, but one of the big arguments for FPTP — that it delivers strong governments — has been proven in recent years to be totally flawed. In the last parliament, a large governing party has shown itself perfectly able to argue with itself and split into numerous factions, research groups, etc (and this has always struck me as slightly grubby ends-justify-means logic anyway).

But there’s something I find I can’t let go about FPTP: I really like its ancient principle of “one constituency, one MP”.

For one thing, it keeps politics grounded. Any proportional system needs bigger constituencies to work (except mine, spoilers) — meaning the link between place and MP is eroded, with multiple people claiming to represent a bigger place. I want MPs to stay connected to practical problems like school places and housing affordability, rather than get lost in abstract ideology. I like that MPs have to engage with their areas to win elections, rather than coasting in on the back of popular support for their party.

The wrong answer

Now, there’s already a system out there designed to solve this problem: the Additional Member System (AMS), which is used for the Scottish Parliament, as well as in Germany and New Zealand (also known as Mixed Member Proportional). People vote twice: for a local candidate, and for a national party. The local candidates get elected, then other MPs are used to “top up” the national parliament so it represents people’s party views.

I don’t hate AMS, but I don’t love it either. You end up with a weird situation where some MPs have lots of responsibilities to a constituency and others don’t. That creates “two tiers”. As one example, shortly before standing down Humza Yousaf criticised Scottish Labour Leader Anas Sarwar for not having a constituency, as if that made him something of a two-bit MP (representing instead the “Glasgow region”). And of course, most AMS systems still tie the top up members to some sort of region, as it would just be odd for them to be totally free floating, so you haven’t eliminated the multiple representatives problem.

Also, if we were to bring in AMS to the UK now, we’d have to add hundreds more MPs, or start forming much bigger constituencies. I’m not in favour of either. Is there a better way?

Introducing… Best Fit Proportional Constituency Allocation (BFPCA)

This got me thinking. What if we kept our constituencies as they are, but decided the number of MPs for each party using national voting proportions? We would then have to find a way of allocating those “party places” to constituencies.

Let’s make it concrete and look at the 2019 election, a classic of the FPTP genre. The Tories got 43.6% of the vote, but a stonking 56.2% of the seats. The SNP got almost twice as many seats as their vote share would indicate. And, as ever, it was the Lib Dems who really got battered, with 11.5% of the vote, but only 1.7% of the seats in Parliament.

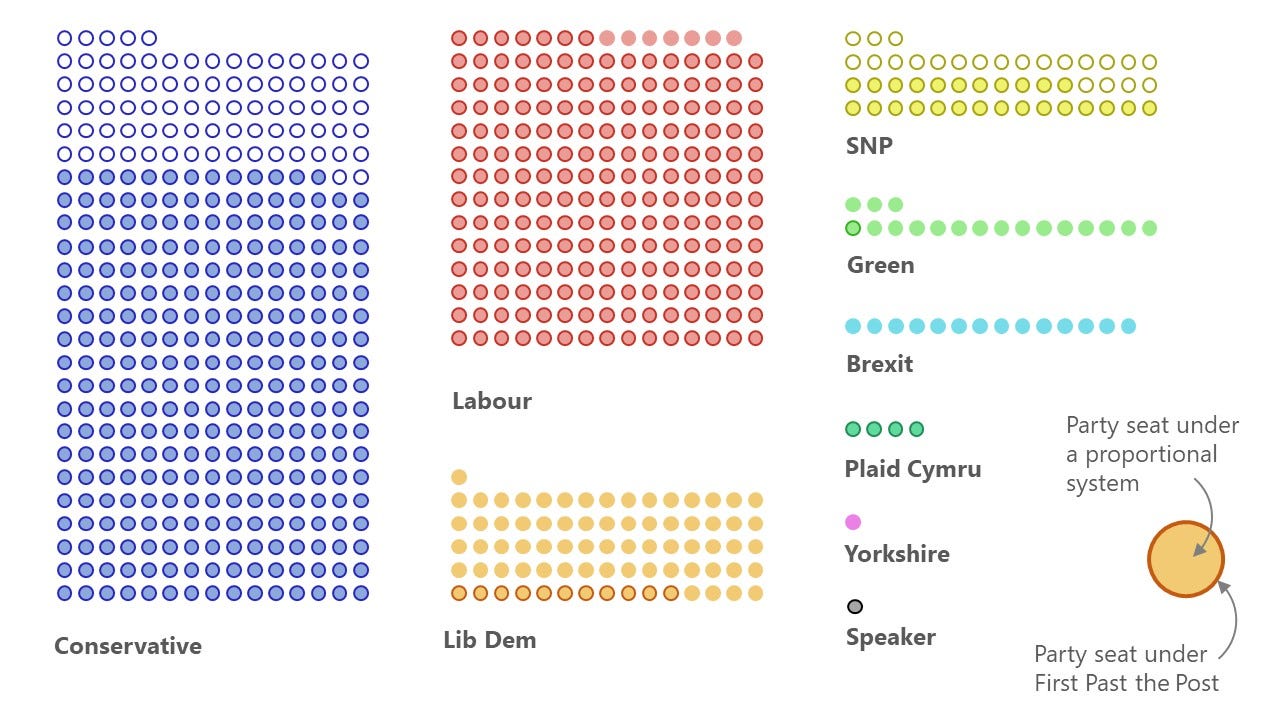

If seats were allocated proportionally it would look like this (I include the number of seats given under FPTP for comparison):

NB I’m leaving out Northern Ireland for simplicity, as all their parties are different.

You can see the big winners from switching to a proportional system are the Lib Dems, Greens, and the Brexit Party; while the big losers are the Conservatives and SNP. The Tories are still the biggest with 283 seats. And at the bottom, the Yorkshire Party make a groundbreaking entry into Parliament with one seat. (There’s a bit of rounding involved — if any wants any more detail on that, ask in the comments).

So let’s say we want this to be the shape of our parliament. Our challenge is this: how can we best allocate these “shadow seats” to constituencies, in order to give us the best fit for what people voted for there?

Of course, we can’t just automatically give each constituency the party most people there voted for: that would just be FPTP again. We also can’t rely on mutant algorithms designed by some maniac economist*: people need to understand how it works for it to command public support. It has to be simple.

Here was my first thought: parties with fewer votes will struggle the most to hold legitimacy in any area. So let’s start with them.

Firstly, there’s the Speaker. He only stood in his constituency of Chorley: he’s duly elected there.

Next up is the Yorkshire Party. They fielded 28 candidates across God’s own country. In almost all the places they stood, they got more than 1% of the vote (which isn’t nothing).

All these votes have secured them one seat in the Parliament. We should therefore give it to them in the seat where they got the highest % share of votes, to give the strongest local legitimacy. That’s Normanton, Pontefract and Castleford — where candidate Laura Walker got 3.7% of the vote. She’s elected!

That may sit a bit uncomfortably — but we have to remember we’re starting with the national vote as sovereign. That has decreed we need a Yorkshire Party MP — and this is the best place for them. And the votes of people in N, P & C who didn’t vote Yorkshire aren’t wasted — they’ll still find a home in the national parliament, which is actually what most voters care about.

(Also, note that BFPCA isn’t a “list” system, which further weakens the link between politicians and the local electorate in some proportional systems. We don’t say to the Yorkshire Party: “You’ve won one seat, so give us your top candidate and we’ll parachute them in there”. Instead we say: “You’ve won one seat, so in the place you got the highest vote share, the candidate you put forward is elected”. The ballot paper looks exactly the same as it currently does).

We then turn to Plaid Cymru. They got enough votes to earn four seats, so we give them the four seats in which they got the highest vote share. These turn out to be the same four seats they won under FPTP. No change there.

After that, it’s the Brexit Party. They earned 14 places, mostly in Yorkshire. We begin to allocate them, starting with the two Barnsley seats, where they came second. But when we get to number 12, there’s a problem — it’s our old friend Normanton, Pontefract and Castleford, which has already been given to the Yorkshire Party. So we skip over that one, meaning they instead get Torfaen, in Wales (their 15th seat by vote share).

Here’s the picture so far…

We keep going. The Greens are up next, who bring Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party to an ignominious end by snatching his Islington North seat, along with thirteen others. Then it’s the SNP, who are much less dominant in Scotland once a proportional system is introduced.

We then give the ecstatic Lib Dems lots of seats, mostly in the South, but a few in Scotland. Of the 65 extras they’ve got under the new system, they were 2nd place in 64 of them.

Then we add in Labour…

…and then the Tories get everything that’s left. But because these are the seats where other parties have had smaller vote shares, they’re mostly ones the Tories came first in anyway.

And that’s it — our final map. Using a pretty simple system we’ve managed to build a parliament that perfectly represents national voting, while giving every constituency one MP.

The legitimacy question

You’ve spotted the issue, of course. Some constituencies end up with an MP who wasn’t the most popular choice in that place. Victories on election night would be haunted by the same anxiety Premier League football fans in an age of VAR feel when their team scores — is it about to be disallowed?

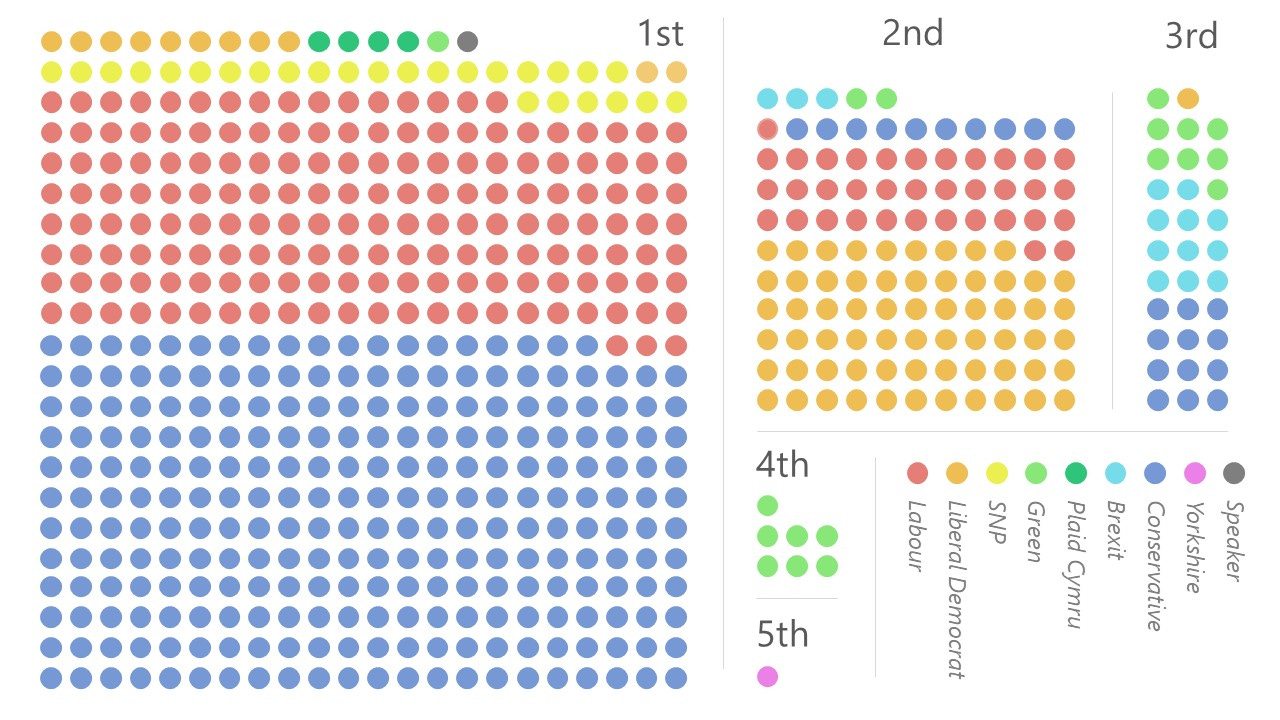

But it’s actually a smaller problem then you’d think. It turns out that in 2019, under BFPCA, just over three-quarters of constituencies would get their first choice MP anyway. And almost all the rest get their second choice. 5% get their third choice, 1% get their fourth choice, and just one seat gets their fifth choice. You’ve guessed it: Normanton, Pontefract and Castleford, a place I think I’ve really put on the map through this post.

Seats by party, and the position their new MP finished in, if 2019 election run by BFPCA

And of course, this is for 2019, an election with a landslide majority. In a more closely fought election, you’d expect the gap between the number of seats under FPTP and a proportional system to be smaller — requiring less reallocation, and fewer constituencies without their first choice for MP.

The logic for you if you live in one of the minority of constituencies without their first choice is this: Because your constituency showed higher than normal support for a smaller party, in our quest to make parliament more representative we’ve chosen them instead. If you didn’t vote for them, your vote still counted — it’s essentially been transported elsewhere, and still goes towards the national parliament. You’ve traded off some of your ability to decide the local MP for a much greater ability to shape the national parliament — a trade I think most people would be willing to make. And the logic for an MP in one of these seats is: you may have slightly less of a local mandate. But your mandate principally comes from all the people across the country who have voted for your party.

But is this really better than FPTP?

Yes, I think so. Here’s why.

FPTP harks back to a time before parties. The call on those who could vote was simply this: which of these people do you most trust to represent you?

Since then, party politics have become dominant. But formally, we still vote for a person rather than a party. If they change party allegiance midway through parliament, that’s tough.

But most voters actually think in party terms — which party, or party leader, do I most like? While some will know their local MP, it’s rare for someone to vote for a local MP whom they like personally but dislike their party. Because if you vote for them, you are supporting their party, whether you want to or not. It’s awkward.

BFPCA is better suited for the times. Mainly, you’re voting for a party. And, unlike FPTP, your vote will definitely count. But your vote does also have a weaker influence on who ends up being MP: the larger your candidate’s vote share, the more likely they are to be elected.

To put it another way, under FPTP people directly choose a local candidate, but can only indirectly influence the national parliament. Under BFPCA, people directly choose the national parliament, and indirectly influence who their local candidate is.

And that links to another nice advantage: the end of safe seat complacency. There aren’t really any truly safe seats, because if a smaller party does well for itself somewhere it can nab the seat. That means MPs need to be always working for votes and trying to represent the full range of their constituents.

A few other bits

By-elections would be run just as they are now. That could mean that by the end of a parliament the % mix looked slightly different to what people voted for at the start, but only marginally.

If you really didn’t want people like the Yorkshire Party in parliament, then you could add in some sort of minimum threshold a party would have to clear to get a seat (as happens in Germany). It would make it a bit less elegant though.

There’s an issue with Northern Ireland: you could have a situation where high or low turnout there meant you ended up with more or less seats going to NI parties than there are seats in the province. That’s a problem, as there’s no crossover between parties, so you could end up with the weird spectre of a Tory MP in Belfast or a Sinn Fein MP in Crewe. This could be simply solved just by running the system separately in Northern Ireland.

Spread the word

As I said at the start, this idea has been on my mind for a long time. It’s possible someone else has come up with it already, though I’m not aware of it if they have.

After quite a long time pondering, I still can’t see anything majorly wrong with BFPCA. I get that the thing of some constituencies not getting their first choice of MP would be hard for people to get their heads around when all we’ve known is FPTP. But there are two really, really big points in its favour:

We get a parliament that properly represents our preferences, with no wasted votes

We can keep local MPs, ensuring better representation of local problems and issues in parliament

The fact that a minority of constituencies won’t always get their top choice seems a relatively small price to pay for these two benefits.

I also think BFPCA might actually be the UK’s only way to getting a proportional system. When voting reform was put to the people back in 2011, it’s telling that the system we were offered — the Alternative Vote — wasn’t a proportional one at all. The idea of getting rid of MPs and constituencies as we know them, in favour of bigger multi-member regions, was seen as more than people would tolerate. So we were instead offered something pretty similar to FPTP, but with some preference ranking as well. (Even the Lib Dems, who demanded the referendum, didn’t really like it).

But BFPCA allows us to keep constituencies as they are, and have a proportional parliament — without having to draft in hundreds of top-up MPs — and keep voting as one simple choice: who do you like best?

So as I finish, a request. Fringe ideas like this one struggle to enter the mainstream (particularly when those putting them forward have shown a very weak commitment to developing a loyal audience of followers on their blog site). I’m not necessarily asking you to agree with me (though I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments). But if you think this idea has enough merit to be worth being part of the conversation, please could you share this post? You could share this link, or my twitter thread on the topic, or just tell someone you know who also finds these things interesting.

Because the 2024 election will undoubtedly produce another parliament that doesn’t properly represent people’s preferences. FPTP forces people who support parties like the Greens or Reform UK into an uncomfortable choice: waste your vote, or compromise. That’s always struck me as unfair, and undemocratic.

But no-one has yet come up with an alternative system that’s acceptable to the UK public. Possibly, just possibly, this is it.

*Admittedly this may be how some would characterise me after reading this post

Interesting, but how do we handle independent candidates?

One other observation is that rather than viewing the country as a whole, each of the 12 regions of the UK are treated separately, thereby ensuring that we do not get a Sinn Fein MP representing Crewe.

Hi Daniel. A very interesting idea worthy of a prize in a different competition, but I prefer the Electoral Reform Society's suggested system to replace FPTP: single transferable vote. Much simpler with, dare I say it, much the same result. Whaddaya think?