That question — thrown down by a new essay prize — should be uppermost in policymakers’ minds at the start of 2024 (Think you can do better? Details here).

It’s hard to argue with the premise. You already know about our dismal productivity statistics and stuttering growth. But these problems run very deep; what single intervention could be so audacious and transformative that it might actually shake us out of our collective torpor?

The entry criteria say they want “punchy takes”. Alright then: we should build a new city.

No, I’m not fantasising about a space age techno-utopia, complete with monorail. But nor do I have a glorified housing estate in mind. This needs all the trimmings: a grand civic building, main public square, central library.

Preposterous? Not really. We did this in the sixties and seventies with Milton Keynes. Although a new “town”, it officially became a city in 2022 — and with 287,000 residents, it deserves the accolade. This new city should aim to grow a bit faster — perhaps 400,000 residents in fifty years.

Poor MK is the butt of many a joke. But those who are serious about boosting UK growth should pay attention: its travel to work area is the eighth most productive in the country (out of 228)1. If we could do it then, why not now?

The need for a mental shift

A new city — done well — could enable a lot of pent-up growth by supplying desperately needed housing and commercial space. It would include a range of housing types, with higher densities at the centre, easing out into the suburbs. But why go this way about growth?

Firstly, there are powerful political forces which stop things being done in and around our towns and cities. People organise to block development, and our planning processes descend into pitched battles. If we want to tackle the housing shortage, it might actually be easier to build a whole new city from scratch than try to win all of these tussles.

That’s the hardheaded reason. But there’s another — less tangible, but more profound — reason, which concerns our national psychology.

In Britain, we’ve started to believe that we can’t get things done any more (the sorry HS2 saga hasn’t helped). A new city could change that. It would be a grand national project, the thing to work on for aspiring civil servants, planners, and architects. It could capture the national imagination like nothing else. There’s a reason Milton Keynes was born at a time of strong economic growth and a broad optimism about the progress of technology: we build new cities when we think the future is bright.

With apologies to fans of architectural modernism, the place I will allow a bit of MK-bashing is design. But it’s not the “arrogance of the present” to say that we really do know how to make better places than we did in the sixties. We’ve studied our favourite historical cities, we know that we need just the right amount of variety, a walkable centre, inviting streets to explore. This new city would have a design committee to oversee it, bringing in global expertise to create a genuinely excellent place to live. Existing villages could be incorporated as neighbourhoods, and the rest of the city would need to be sympathetic to them.

The fusion factor

So where would it go to have the most impact? Here are some criteria:

A location that could quickly generate new jobs

An area in need of investment (and one which would broadly welcome, not fight, it)

Good accessibility to London, for businesses and professionals who need the connection

Close enough to other cities to enjoy the benefits of trade and agglomeration — but not so close that it becomes a dormitory for them

Not in a protected landscape, or area of particular environmental importance

You would, of course, have an evaluation process and assess various proposals, but since we’re after punchy takes:

Here. It should go here, to the east of Retford. (And no, there’s no personal interest).

Source: Google maps

This place has it all. The area struggles with low productivity (almost 30% below UK levels2) and would benefit from a boost in business growth and new housing (point 2, above). It’s on the A1 and the East Coast Main Line – rail journey times from Retford to central London come under the magic 90-minute threshold (3). It’s roughly an hour’s drive from Nottingham and Sheffield (4). And it’s not in a national park or other designation (5). It also benefits from being pretty flat (so easy to build on), and the Trent, which runs along its eastern edge, would provide a good source of water.

But the real clincher is point 1 — the potential for new jobs. Firstly, you could generate a big load here by riding the wave of Britain’s biggest boom industry right now: logistics. Just as the West Coast Main Line is getting its rail freight hub, this would be a good spot for the East Coast equivalent. Jobs in the sector are relatively well paying (especially at the cutting edge) — and would get the new city off to a good start.

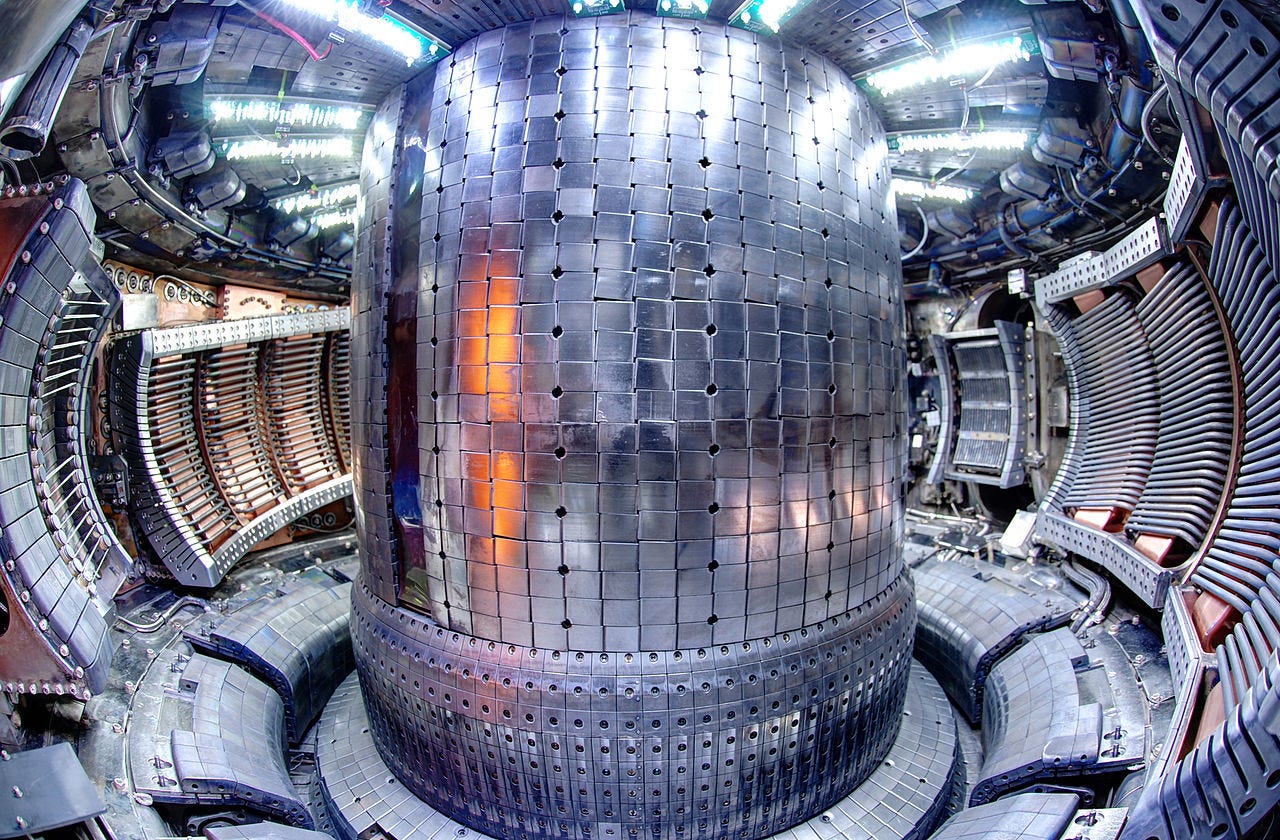

More exciting, though, is what’s happening on the city’s northern frontier. With little fanfare, the village of West Burton has been chosen to host a spherical tokamak — which will be the world’s most advanced nuclear fusion prototype. In concept, fusion is the abundance technology par excellence: our most audacious bet for a clean, prosperous future.

The development of fusion in a largely rural location is a rare opportunity to create a new city with a high-skills jobs base. Construction on the tokamak is taking place this decade, so the ideal time to start planning is now. Premises for supply chain businesses, fast transit links to the city centre, and good meeting places to share ideas (pubs, parks, etc.) will all be essential.

I expect my dissenters will come from two camps. First, the environmentalists, who will object to building on such a large scale. These are understandable concerns, but already the acute need for housing is putting pressure on environmental protections. A new city would allow you to better navigate trade-offs: designing in nature corridors and biodiversity protection from the beginning, with all housing built to stringent water and energy saving standards.

The second are residents of other cities, who might (understandably) feel that investment would be better spent there. Absolutely, the road to a prosperous Britain goes through our cities, which by and large lag behind their continental peers. But this is a false trade-off — part of the “either/or” mentality that so often leads to “neither/nor”. Investment for the new city would come from a range of sources: developer contributions, business relocations, even land value uplift. The government would have to spend upfront, of course, but over the long-term a successful city will more than pay back to the exchequer.

There’s probably a third group too, who scoff at the whole enterprise. Many will say that in this day and age we simply can’t build new cities any more.

Which is exactly why we should.

I usually write economics and policy articles for The Mill, The Tribune, The Post, and The Dispatch — a family of publications working to revive local journalism in the UK. I was previously an economic consultant with Metro Dynamics.

https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/labourproductivity/datasets/subregionalproductivitylabourproductivityindicesbylocalauthoritydistrict. See table A1. Bassetlaw, the local authority, has a productivity index of 71.2 (compared to the UK at 100)

I like the idea and I think the location is great (I live in Sheffield).

However, I’ve had a similar, but more extensive idea for some time now. Do what you suggest near Retford but do it in, or close to, some of our least historic, and often struggling, seaside towns. I’m talking about places like Blackpool/Fleetwood, Skegness and Rhyl etc rather than Whitby, Brighton and Llandudno.

Let’s focus on getting some of our newer resorts, those that can’t rely on their history to bring in visitors, a much greater diverse economy. Being located on the coast means access to ports should be quick and easy and the extra tax revenue from new industries and housing should help pay for the inevitable sea defences that are going to be needed in the future. I would like to see at least a doubling of the population of these areas within 10 to 15 years of such a scheme being implemented.

Presumably much of the time the new city will be underwater from Trent floods